Vermouth 101

Introduction

Welcome to Vermouth 101. The intent of these pages is to demystify vermouth, primarily for the American audience. Vermouth has been ubiquitous in the USA for well over a century, but few Americans understand what it is, and some have even maligned it. Coincidentally, we’re living in a new “golden age” of vermouth with classic brands revitalized and new, experimental vermouths emerging both from the traditional European sources and from upstart American winemakers. Now is a great time to raise your vermouth awareness! While we’re here, we’ll also look at quinquina and americano, two cousins of vermouth that were all but forgotten in the US, yet are also reemerging with vigor.

Understanding aperitif wines

To understand vermouth, one first must understand aperitif wines. Aperitif derives from the Latin aperire, which is the verb “to open,” in the sense of opening up the appetite. All true aperitifs carry a bittersweet character that stimulates the production of gastric juices and promotes appetite.

Aperitif wines are aromatized wines. Aromatized means that the wine has been infused with botanicals that add flavor and color. The aperitif wine category includes all vermouths, quinquinas, americanos, and a smattering of other proprietary formula wine products.

| Fortified Wines (non-aperitif wines) | Fortified & Aromatized Wines (aperitif wines) |

|---|---|

| Sherry Port Madeira Marsala (some) Pineau des Charentes | Vermouth Quinquina Americano Barolo Chinato various vino amaros |

Vermouth, quinquina and americano are also fortified wines. Fortified means the alcohol percentage of the wine has been raised through the addition of spirits (a fairly neutral grape brandy is ideal in most cases). Almost all these wines have a white wine or mistelle base. Mistelle is the result of adding alcohol to the juice of crushed grapes rather than fermenting them to produce alcohol. The mistelle approach yields a sweeter base (because the fructose has not been converted to alcohol) and may lend a more “fresh fruit” characteristic to some products. All but a handful of red/dark/opaque aperitif wines achieve their coloration through other ingredients rather than the wine itself, namely caramel color (burnt sugar).

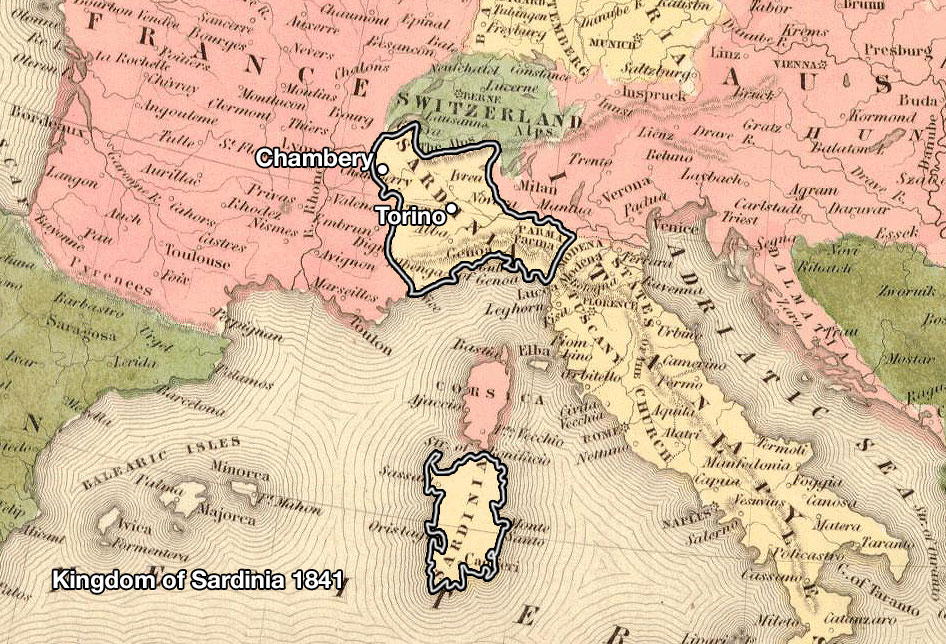

Geographically, the cradle of vermouth is the ethnically Italian Piemonte and the ethnically French Savoy regions, which, in the 18th Century comprised the mainland territory of the Kingdom of Sardinia.

In addition to political and economic ties, these regions shared the local wine production, wealth, and the rich botanical diversity of the Alpine foothills necessary to produce vermouth and related beverages. (By the 1861, the Kingdom of Sardinia had gobbled up the rest of the peninsula to create what we know today as Italy, losing the Savoy region permanently to France by treaty.)

The aperitif wines of this area evolved from two imperatives: the flavoring of local wines to make them more commercially valuable and the ancient trade in folk medicines and tonics. These wines are delicious and packed with “medicinal” botanicals (now enjoyed for their flavors and appetite-enhancing effects rather than as cures).

Large scale commercial aperitif production emerged in the mid-1800s with a focus on craft and consistency and an eye toward export markets. The major ports of Marsielles, Genoa and Venice played key roles for the importation of exotic botanicals (spice trade) and the export of product to new markets, especially the Americas. Traditionally, these products were named for the entrepreneurs that created them. Today, several of these names are amongst the greatest brands in this history of spirits.

Aperitif wines are relatively low in alcohol content when compared to other spirits, but a bit higher than straight wine. Aperitif wines are comparable strength-wise to non-aperitif fortified wines like Port, Madeira, or Sherry. Also, like other fortified wines, aperitif wines are typically enjoyed in smaller servings than straight wine (perhaps 2-3 oz).

| Approx. Alcohol by Volume | Beverage |

|---|---|

| 1-4% | preservative alcohol |

| 3-10 | beers, ciders and beer-related ferments |

| 10-14 | straight wine |

| 13-24 | fortified and aperitif wines |

| 25-40 | underproof spirits (some vodkas and styles of shōchū) |

| 15-50 | liqueurs |

| 40-50 | spirits |

| 50+ | high proof spirits |

The vast majority of aperitif wines are reasonably priced ($10-25 for 750ml). In liquor stores, aperitif wines are typically found on shelves near sherries and ports, although this is not always the case. Unfortunately, these days, even the best liquor stores are unlikely to have more than a haphazard assortment of aperitifs wines, and are even less likely to have anyone on staff that actually knows anything useful or correct about these products. A key point to keep in mind when shopping: there is no such thing as “the best” amongst these or any other liquors. We are blessed with a wealth of fine products with individual characters, and that diversity should be celebrated.

Vermouth

The word “vermouth” derives from “wormwood”, and is inherited from earlier Hungarian and German wormwood-infused wines of the same name. At least since the early 19th Century, what we mean by “vermouth” is a refinement incorporating the most desirable elements of both these older wines and various other traditions: a moderately sweet, herbacious, compounded beverage. Wormwood remains vermouth’s starting point: its principal, defining botanical. Commercialization began in the late 18th Century in Torino, Italy. In ensuing years, other interpretations of the idea emerged in Chambéry (Savoy), Lyon/Marseilles and Spain.

In the United States, vermouth imported from Italy became wildly popular beginning in the 1870s, and ever since, this “Italian” vermouth has been strongly associated with the Manhattan cocktail. By contrast, Europeans commonly sip this aperitif neat or over a little ice. The dry style, that emerged first in France, achieved similar popularity in the US almost concurrently, eventually becoming strongly associated with the Martini cocktail. Dry vermouth, especially that in the Marseilles style, also has a strong tradition in the regional kitchen as a cooking ingredient, and it makes a particularly nice alternative to white wine in pan sauces.

These same regions have historically produced other styles of vermouth in the past, not all of which have achieved international success. Two examples that have—both from Torino—are vermouth alla vaniglia (vermouth with vanilla) and vermouth con bitter (vermouth with extra bitters). Vermouth Chinato (vermouth with added quinine) is making a 21st Century comeback. Blanc (white) vermouth is a late-19th Century innovation from Chambèry. Bianco vermouth is the bolder Italian riff on white vermouth that roughly dates to the turn of the 20th Century, but remained obscure until achieving abrupt and massive popularity in 21st Century Eastern Europe.

A footnote—but one of growing significance in the marketplace—is Spanish vermouth. From the late 19th Century on, Spanish producers—mostly concentrated around Reus (in Catalonia) and often from Italian immigrant lineage—have been making their vermut in the relative obscurity, restrained by war and dictatorship. Their vermouths, largely comparable to sweet, red Italian vermouth, tend to have a less Alpine and more Mediterranean character.

| Torino/“Italian vermouth” | ||

|---|---|---|

| rosso/“sweet vermouth”/ vermouth di torino |

Martini & Rossi Rosso Cinzano Rosso Cocchi Vermouth di Torino &tc. |

|

| vermouth all vaniglia | Carpano Antica Formula | |

| vermouth con bitter | Carpano Punt e Mes | |

| vermouth chinato | Alessio Vermouth Chinato Cocchi “Dopo Teatro” Vermouth Amaro Martini Gran Lusso |

|

| vermouth bianco | Martini Bianco Carpano Bianco &tc. |

|

| Marseilles/“French vermouth” | ||

| “dry vermouth” | Noilly Prat Original Dry Noilly Prat Extra Dry |

|

| Chambéry | ||

| Chambéry vermouth | Dolin Rouge Routin Original Rouge |

|

| Chambéry blanc | Dolin Blanc Routin Blanc |

|

| Chambéry dry | Dolin Dry Routin Dry |

|

| Spain/Vermut de Reus/Vermut de Jerez | ||

| rojo | Miro Vermut de Reus Vermouth Perucchi Yzaguirre Vermouth |

|

| other | De Muller Reserva Priorat Natur Vermut |

|

Today, almost all traditional vermouth producers manufacture some form of red and dry vermouths, and many also produce a white vermouth. “Me too” products have a long history in this market. It is generally fair to say that French producers are more esteemed for the lighter, dry vermouths, and Italian producers are more esteemed for the red, spicy Torino-inspired vermouths, but all commercial vermouths are proprietary formulas, and it is their unique botanicals and flavor profiles that distinguish them. Some may be better, some lesser, although even those often judged amongst the “best” may not be best in all circumstances. It is particularly important to not fall into the trap of comparing vermouths to some platonic ideal: it’s no more reasonable to expect all vermouths of one style to taste the same than it is to expect all bourbons or gins to taste the same. Celebrate the diversity of choice and let your own taste be your guide.

Non-traditional Vermouth

So far, we’ve been talking about traditional vermouth: European products with Alpine roots (and their imitators). Various new contemporary non-traditional styles also can be found in some markets.

What some call “Western Dry”—a de-facto style begun in California in the late 1990s—is already fairly well established. These are small production aperitif wines labeled as vermouth but which, in most cases, are otherwise unrecognizable as such. These products tend to be “wine-forward” and feature drastically divergent botanical components.

The resurgent market is also producing other novel, non-traditional ideas. Some represent contemporary innovation from traditional vermouth producers. Others, such as the new vermouths out of Jerez based on sherry, are crossover forays comparable to the “Western Dry” phenomenon. Most of these are just beginning to test the market in the 2010s.

| United States | ||

|---|---|---|

| “Western Dry” | Vya Sweet Vermouth Imbue Vermouth Atsby Amberthorn &tc. |

|

| “modern” | ||

| Rosé | Martini Rosato | |

| Amber | Noilly Prat Ambré | |

| Andalusian | Lustau Vermut Cruz Conde Rojo Reserva 1902 &tc. |

|

Quinquina & Americano

There are a number of venerable aperitif wines that aren’t vermouths, but have much in common with vermouth. One group of these wines is known as “quinquina” (kenKEEnah), because historically these wines feature (or at least include) Peruvian chinchona bark (“quina” in the native Quechua tongue, “china” [KEE-nah] in italian, and possibly Anglicized as china [chai-nuh]) amongst their botanicals. Chinchona bark is the primary source of quinine (the pharmaceutical and taste component of Tonic water). Quinine became the wonder drug of the 18th Century when colonizing Europeans realized that it was beneficial in warding off malaria, and for a while, Europeans were adding quinine to anything and everything. A major market for quinquina was France’s protracted campaign in Algeria, which held large numbers of French troops and administrators in tropical peril. Some quinquina was specifically produced with the French foreign legion in mind.

Americano refers to the word amer (bitter). Where quinquina’s defining flavor is quinine, Americano’s is both gentian and wormwood. Historian François Monti hypothesizes that Americano—which seems to have emerged in the 1890s—may be a commercial elaboration on “vermouth con bitter” (vermouth with added gentian), a Turinese cafe tradition documented by Arnaldo Strucchi.

Traditional vermouth, quinquina, and americano all draw from much the same pool of botanicals, and their classification or style is a question of the intent behind the proprietary formluation. Both Quinquina and Americano can come in various colors, such as deep red, straw or even clear (colorless). Almost all are based on white wine mistelle, although one notable exception is Byrrh, which is based on a red wine mistelle.

Quinquinas and Americanos serve a similar function to vermouths: they are excellent aperitifs on their own, and they make fine components of mixed drinks.

A conundrum of colors and labels

You will find that vermouths, quinquinas and americanos are often sold in different “colors” under the same brand. The color ostensibly refers to the hue of the liquor itself, which in vermouth is most commonly reddish brown, colorless (“white”) or straw-colored, although other possibilities exist, such as rosé. The naming and labeling of these products is not always straightforward.

Originally, vermouth brands were established around a singular product and color was not really a major marketing factor. Some vermouth may have been tinted with black walnut, or simply by the botanicals employed in aromatizing them. Caramel color may have been employed here or there for color consistency across bottlings (Strucchi, Il Vermouth di Torino, 1907). But color was not otherwise much discussed.

Meanwhile, as the market matured, those brands that sought to distinguish themselves innovated. In Savoy and Marseilles, new commercial vermouths surfaced that had significantly different flavor profiles from those in Turin. The export market exploded abroad in the mid-19th Century—particularly to the United States and South America—and so the notion of “Italian vermouth” and “French vermouth” arose, with each dominated by a runaway market leader: Martini & Rossi and Noilly Prat, respectively. None of these products were labeled “Italian vermouth” or “French vermouth”, but their Italian or French origin was the second-most obvious thing about them after the brand name. The French vermouths were typically drier (particularly those from Noilly, which were also distinctly oxidized) and the dry Noilly characteristic came to define the French style through association. Historian François Monti has shown that, as early as the 1860s, terminology like “vermuth sec” crops up in literature, but in practical usage, it was just “French Vermouth”.

In remote Chambéry, their less-known vermouth wasn’t oxidized like Noilly, and wasn’t necessarily as dry. Around 1881, the producer Comoz coined the term “blanc vermouth”, and color became a marketing factor. Coincidentally, Chambéry’s filtered, distinctly Alpine vermouth gradually became better-distributed and grew in influence, inspiring other producers such as Martini & Rossi to develop their own “white vermouth” (bianco) by 1910.

By the early 20th Century, producers were leveraging their brands across diverse vermouth product lines. Monti (La Conca 5.1, November 22, 2017) has shown that, around World War I, Italian producers began increasing the caramel coloring of their Vermouth di Torino and labeling it “rosso”. Coloration wound up the new method of product differentiation, and a de facto nomenclature emerged:

| English | Italian | French | Spanish | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| red/brown | red/sweet/“Italian” | rosso | rouge | rojo |

| clear/colorless | white | bianco | blanc | blanco |

| straw | dry/“French” | dry | sec/dry | seco/dry |

| pink | rosé | rosato | rosé | rosado |

Most (not all) vermouth today is labeled with one of these terms. A few manufacturers reject this color-based classification and either employ their own naming scheme or—least helpfully—slap the same label on all their products and leave it up to the buyer to sort out which is which.

Unfortunately, the color of vermouth doesn’t necessarily mean a great deal. A red vermouth indicates a brand’s entry into the red vermouth market segment, and while that sets certain expectations in terms of flavor and performance, it doesn’t guarantee that the product has any great similarity to the original Vermouth di Torino style. All you can really presume is that it is reddish or brown and probably on the sweet side. You can hope it makes a good Manhattan. Vermouth that is labeled white is nearly colorless, on the sweet side, and probably has different botanical emphasis from whatever the same brand’s red vermouth possesses. Vermouth labeled as dry is usually straw-colored and somewhat less sweet, at least in comparison to whatever other vermouths that particular brand might offer. You can hope it pairs well with gin in a Martini Cocktail. However, in all cases, the actual botanicals, flavors and character of the product can only be ascertained by tasting it and testing it out.

Like the original vermouth producers, quinquina and americano brands were generally created around a single product. Some quinquina producers eventually felt obliged (for marketing reasons) to come up with “new colors” to add to their brands. Consequently, you’ll find both a straw-colored and a red-colored Lillet product on today’s shelves; although the labels are identical on both bottles, the contents are not. Dubonnet and Cocchi Americano are other examples of this peculiar market-driven phenomenon.

Serving Aperitif Wines

Aperitif wines are ready to serve from the bottle. In Europe, they are primarily thought of as a stand-alone aperitif, served in a 2-3 oz (6-9 cl) pour, neat, chilled, or over ice. In the United States, vermouths and quinquinas are primarily served in mixed drinks. We recommend you enthusiastically explore both approaches.

Storage & Care

As with other wines, aperitif wines oxidize once they’re opened. They may take on different flavor characteristics in as little as 15-20 minutes after opening! While open bottles of aperitif wines tend to gradually lose their more refined qualities over time, they have just enough alcohol in them that they tend to take weeks or even months to go decisively bad. Open aperitif wines can keep reasonably well if they are tightly capped, in the refrigerator (or a cool place), and away from light. The wine may not be quite as good down the road as when first opened, but it will still be usable (especially for cooking).

The longevity of aperitif wines may be extended by using a “wine pump” or inert gas system to reduce the oxygen in the bottle. When possible, it can be advantageous to buy small bottles (so as to replace them more frequently.)

Aperitif wines do not tend to sell in high volume in the United States, so there is some risk of buying bottles that have been sitting in the distributor’s warehouses or retail stores for a long time under less-than-optimal conditions; while old product is seldom ruined, it may have lost some of its joi-de-vivre. Avoid dusty bottles, especially those with out-of-date labeling.

Further Reading

There’s not a great deal of literature on this topic—particularly not in English—and much of what is available tends to contain misinformation. Here we are endeavoring to correct the misinformation, but we are admittedly heavily reliant on an accumulation of facts and oral statements from industry participants. Far and away, the current state of the art is represented by François Monti’s El Gran Libro del Vermouth (Ediciones B. S. A, 2015). As of this writing, this book is only available in Spanish, but it is the current authority. If you can parse Italian, one interesting historical source to look at is Arnaldo Strucchi’s Il Vermouth di Torino (1907), available in its entirety on Google Books. For further primary research, you may want to look up Maynard Andrew Amerine’s Vermouth: an annotated bibliography (1974).

For further discussion on aperitif wines and their uses in mixed drinks, please visit The Chanticleer Society.